“Ranch and Mission Days in Alta California,” by

Guadalupe Vallejo

“Ranch and Mission Days in Alta California,” by

Guadalupe Vallejo

“Life in California Before the Gold Discovery,” by John

Bidwell

William T. Sherman and Early Calif. History

William T. Sherman and the Gold Rush

California Gold Rush Chronology 1846 - 1849

California Gold Rush Chronology 1850 - 1851

California Gold Rush Chronology 1852 - 1854

California Gold Rush Chronology 1855 - 1856

California Gold Rush Chronology 1857 - 1861

California Gold Rush Chronology 1862 - 1865

An Eyewitness to the Gold Discovery

Military Governor Mason’s Report on the Discovery of

Gold

“A Rush to the Gold Washings” – From the California

Star

“The Discovery – as Viewed in New York and

London”

Steamer Day in the 1850s

Sam Brannan Opens New Bank - 1857

|

William T. Sherman and Early California History

In chapter II of his memoirs, Sherman describes life in Upper

California, and tells of his experiences at Monterey, his visit to the

newly-named San

Francisco, and the last of the Mexican War fought in Lower California. Sherman’s

adventures in California began in January 1847, after a long trip around the Horn to

Monterey.

All

the necessary supplies being renewed in Valparaiso, the voyage was resumed. For nearly

forty days we had uninterrupted favorable winds, being in the “trades,” and, having settled

down to sailor habits, time passed without notice. We had brought with us all the books we

could find in New York about California, and had read them over and over again: Wilkes’s

“Exploring Expedition”; Dana’s “Two Years before the Mast”; and Forbes’s “Account of

the Missions.” It was generally understood we were bound for Monterey, then the capital

of Upper California. We knew, of course, that General [Stephen Watts] Kearny was en

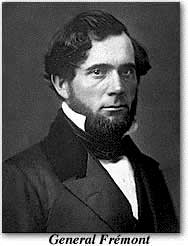

route for the same country overland; that [John] Frémont was there with his

exploring party; that the navy had already taken possession, and that a regiment of

volunteers, Stevenson’s, was to follow us from New York; but nevertheless we were

impatient to reach our destination. About the middle of January the ship began to approach

the California coast, of which the captain was duly cautious, because the English and

Spanish charts differed some fifteen miles in the longitude, and on all the charts a current of

two miles an hour was indicated northward along the coast.

At last land was made one

morning, and here occurred one of those accidents so provoking after a long and tedious

voyage. Macomb, the master and regular navigator, had made the correct observations, but

Nicholson during the night, by an observation on the north star, put the ship some twenty

miles farther south than was the case by the regular reckoning, so that Captain Bailey gave

directions to alter the course of the ship more to the north, and to follow the coast up, and

to keep a good lookout for Point Piños that marks the location of Monterey Bay. The usual

north wind slackened, so that when noon allowed Macomb to get a good observation, it

was found that we were north of Año Nuevo, the northern headland of Monterey

Bay. The ship was put about, but little by little arose one of those southeast storms so

common on the coast in winter, and we buffeted about for several days, cursing that

unfortunate observation on the north star, for, on first sighting the coast, had we turned for

Monterey, instead of away to the north, we would have been snugly anchored before the

storm. But the southeaster abated, and the usual northwest wind came out again, and we

sailed steadily down into the roadstead of Monterey Bay. This is shaped somewhat like a

fish-hook, the barb being the harbor, the point being Point Piños, the

southern headland.

Slowly the land came out of the water, the high mountains about Santa

Cruz, the low beach of the Salinas, and the strongly-marked ridge terminating in the

sea in a point of dark pine-trees. Then the line of whitewashed houses of adobe,

backed by the groves of dark oaks, resembling old apple-trees; and then we saw two

vessels anchored close to the town. One was a small merchant-brig and another a

large ship apparently dismasted.

At last we saw a boat coming out to meet us, and when it

came alongside, we were surprised to find Lieutenant Henry Wise, master of the

Independence frigate, that we had left at Valparaiso. Wise had come off to pilot us to our

anchorage. While giving orders to the man at the wheel, he, in his peculiar fluent style, told

to us, gathered about him, that the Independence had sailed from Valparaiso a week after us

and had been in Monterey a week; that the Californians had broken out into an insurrection;

that the naval  fleet under Commodore Stockton was all down the coast about San

Diego; that General Kearny had reached the country, but had had a severe battle at San

Pascual, and had been worsted, losing several officers and men, himself and others

wounded; that war was then going on at Los Angeles; that the whole country was full of

guerrillas, and that recently at Yerba Buena the alcalde, Lieutenant Bartlett, United States

Navy, while out after cattle, had been lassoed, etc., etc. Indeed, in the short space of time

that Wise was piloting our ship in, he told us more news than we could have learned on

shore in a week, and, being unfamiliar with the great distances, we imagined that we

should have to debark and begin fighting at once. Swords were brought out, guns oiled

and made ready, and every thing was in a bustle when the old Lexington dropped her

anchor on January 26, 1847, in Monterey Bay, after a voyage of one hundred and

ninety-eight days from New York. fleet under Commodore Stockton was all down the coast about San

Diego; that General Kearny had reached the country, but had had a severe battle at San

Pascual, and had been worsted, losing several officers and men, himself and others

wounded; that war was then going on at Los Angeles; that the whole country was full of

guerrillas, and that recently at Yerba Buena the alcalde, Lieutenant Bartlett, United States

Navy, while out after cattle, had been lassoed, etc., etc. Indeed, in the short space of time

that Wise was piloting our ship in, he told us more news than we could have learned on

shore in a week, and, being unfamiliar with the great distances, we imagined that we

should have to debark and begin fighting at once. Swords were brought out, guns oiled

and made ready, and every thing was in a bustle when the old Lexington dropped her

anchor on January 26, 1847, in Monterey Bay, after a voyage of one hundred and

ninety-eight days from New York.

Every thing on shore looked bright and beautiful, the

hills covered with grass and flowers, the live-oaks so serene and homelike, and the

low adobe houses, with red-tiled roofs and whitened walls, contrasted well with the

dark pinetrees behind, making a decidedly good impression upon us who had come so far

to spy out the land. Nothing could be more peaceful in its looks than Monterey in January,

1847. We had already made the acquaintance of Commodore Shubrick and the officers of

the Independence in Valparaiso, so that we again met as old friends. Immediate

preparations were made for landing, and, as I was quartermaster and commissary, I had

plenty to do. There was a small wharf and an adobe custom-house in possession of

the navy; also a barrack of two stories, occupied by some marines, commanded by

Lieutenant Maddox; and on a hill to the west of the town had been built a two-story

block-house of hewed logs occupied by a guard of sailors under command of

Lieutenant Baldwin, United States Navy. Not a single modern wagon or cart was to be had

in Monterey, nothing but the old Mexican cart with wooden wheels, drawn by two or three

pairs of oxen, yoked by the horns. A man named Tom Cole had two or more of these, and

he came into immediate requisition.

The United States consul, and most prominent man

there at the time, was Thomas O. Larkin, who had a store and a pretty good

two-story house occupied by his family. It was soon determined that our company was

to land and encamp on the hill at the block-house, and we were also to have

possession of the warehouse, or custom-house, for storage. The company was

landed on the wharf, and we all marched in full dress with knapsacks and arms, to the hill

and relieved the guard under Lieutenant Baldwin. Tents and camp equipage were hauled

up, and soon the camp was established. I remained in a room at the custom-house,

where I could superintend the landing of the stores and their proper distribution.

I had

brought out from New York twenty thousand dollars commissary funds, and eight

thousand dollars quartermaster funds, and as the ship contained about six months’ supply

of provisions, also a saw-mill, grist-mill, and almost every thing needed, we

were soon established comfortably. We found the people of Monterey a mixed set of

Americans, native Mexicans, and Indians, about one thousand all told. They were kind and

pleasant, and seemed to have nothing to do, except such as owned ranches in the country

for the rearing of horses and cattle. Horses could be bought at any price from four dollars

up to sixteen, but no horse was ever valued above a doubloon or Mexican ounce (sixteen

dollars). Cattle cost eight dollars fifty cents for the best, and this made beef net about two

cents a pound, but at that time nobody bought beef by the pound, but by the carcass.

Game of all kinds–elk, deer, wild geese, and ducks–was

abundant; but coffee, sugar, and small stores, were rare and costly.

There were some half-dozen shops or stores, but their shelves were empty. The

people were very fond of riding, dancing, and of shows of any kind. The young fellows

took great delight in showing off their horsemanship, and would dash along, picking up a

half-dollar from the ground, stop their horses in full career and turn about on the

space of a bullock’s hide, and their skill with the lasso was certainly wonderful. At full

speed they could cast their lasso about the horns of a bull, or so throw it as to catch any

particular foot. These fellows would work all day on horseback in driving cattle or catching

wild-horses for a mere nothing, but all the money offered would not have hired one

of them to walk a mile. The girls were very fond of dancing, and they did dance gracefully

and well. Every Sunday, regularly, we had a baile, or dance, and sometimes

interspersed through the week.

I remember very well, soon after our arrival, that we were all invited to witness a play

called “Adam and Eve.” Eve was personated by a pretty young girl known as Dolores

Gomez, who, however, was dressed very unlike Eve, for she was covered with a petticoat

and spangles. Adam was personated by her brother–, the same who has since

become somewhat famous as the person on whom is founded the McGarrahan claim. God

Almighty was personated, and heaven’s occupants seemed very human. Yet the play was

pretty, interesting, and elicited universal applause. All the month of February we were by

day preparing for our long stay in the country, and at night making the most of the balls

and parties of the most primitive kind, picking up a smattering of Spanish, and extending

our acquaintance with the people and the costumbres del pais. I can well recall that

[Lt. Edward Otho Cresap] Ord and I, impatient to look inland, got permission and started

for the Mission of San Juan Bautista. Mounted on horses, and with our carbines, we took

the road by El Toro, quite a prominent hill, around which passes the road to the south,

following the Salinas or Monterey River.

After about twenty miles over a sandy country

covered with oak-bushes and scrub, we entered quite a pretty valley in which there

was a ranch at the foot of the Toro. Resting there a while and getting some information, we

again started in the direction of a mountain to the north of the Salinas, called the Gavillano.

It was quite dark when we reached the Salinas River, which we attempted to pass at several

points, but found it full of water, and the quicksands were bad. Hearing the bark of a dog,

we changed our course in that direction, and, on hailing, we were answered by voices

which directed us where to cross. Our knowledge of the language was limited, but we

managed to understand, and to flounder through the sand and water, and reached a small

adobe house on the banks of the Salinas, where we spent the night. The house was a single

room, without floor or glass; only a rude door, and window with bars. Not a particle of

food but meat, yet the man and woman entertained us with the language of lords, put

themselves, their house, and every thing, at our “disposition,” and made little barefoot

children dance for our entertainment. We made our supper of beef, and slept on a bullock’s

hide on the dirt-floor. In the morning we crossed the Salinas Plain, about fifteen

miles of level ground, taking a shot occasionally at wild-geese, which abounded

there, and entering the well-wooded valley that comes out from the foot of the

Gavillano. We had cruised about all day, and it was almost dark when we reached the

house of a Señor Gomez, father of those who at Monterey had performed the parts

of Adam and Eve. His house was a two-story adobe, and had a fence in front. It

was situated well up among the foot-hills of the Gavillano, and could not be seen

until within a few yards. We hitched our horses to the fence and went in just as Gomez was

about to sit down to a tempting supper of stewed hare and tortillas. We were officers and

caballeros and could not be ignored. After turning our horses to grass, at his

invitation we joined him at supper. The allowance, though ample for one, was rather short

for three, and I thought the Spanish grandiloquent politeness of Gomez, who was fat and

old, was not over-cordial. However, down we sat, and I was helped to a dish of

rabbit, with what I thought to be an abundant sauce of tomato. Taking a good mouthful, I

felt as though I had taken liquid fire; the tomato was chile colorado, or red pepper,

of the purest kind. It nearly killed me, and I saw Gomez’s eyes twinkle, for he saw that his

share of supper was increased. I contented myself with bits of the meat, and an abundant

supply of tortillas. Ord was better case-hardened, and stood it better.

We staid at

Gomez’s that night, sleeping, as all did, on the ground, and the next morning we crossed

the hill by the bridle-path to the old Mission of San Juan Bautista. The Mission was

in a beautiful valley, very level, and bounded on all sides by hills. The plain was covered

with wild-grasses and mustard, and had abundant water. Cattle and horses were

seen in all directions, and it was manifest that the priests who first occupied the country

were good judges of land. It was Sunday, and all the people, about a hundred, had come to

church from the country round about. Ord was somewhat of a Catholic, and entered the

church with his clanking spurs and kneeled down, attracting the attention of all, for he had

on the uniform of an American officer. As soon as church was out, all rushed to the

various sports. I saw the priest, with his gray robes tucked up, playing at billiards, others

were cock-fighting, and some at horse-racing.

My horse had become lame,

and I resolved to buy another. As soon as it was known that I wanted a horse, several came

for me, and displayed their horses by dashing past and hauling them up short. There was a

fine black stallion that attracted my notice, and, after trying him myself, I concluded a

purchase. I left with the seller my own lame horse, which he was to bring to me at

Monterey, when I was to pay him ten dollars for the other. The Mission of San Juan bore

the marks of high prosperity at a former period, and had a good pear-orchard just

under the plateau where stood the church.

After spending the day, Ord and I returned to

Monterey, about thirty-five miles, by a shorter route. Thus passed the month of

February, and, though there were no mails or regular express, we heard occasionally from

Yerba Buena and Sutter’s Fort to the north, and from the army and navy about Los Angeles

at the south. We also knew that a quarrel had grown up at Los Angeles, between General

Kearny, Colonel Frémont, and Commodore Stockton, as to the right to control

affairs in California. Kearny had with him only the fragments of the two companies of

dragoons, which had come across from New Mexico with him, and had been handled very

roughly by Don Andreas Pico, at San Pascual, in which engagement Captains Moore and

Johnson, and Lieutenant Hammond, were killed, and Kearny himself wounded. There

remained with him Colonel Swords, quartermaster; Captain H. S. Turner, First Dragoons;

Captains Emory and Warner, Topographical Engineers; Assistant Surgeon Griffin, and

Lieutenant J. W. Davidson. Frémont had marched down from the north with a

battalion of volunteers; Commodore Stockton had marched up from San Diego to Los

Angeles, with General Kearny, his dragoons, and a battalion of sailors and marines, and

was soon joined there by Frémont, and they jointly received thewas soon joined

there by Frémont, and they jointly received the surrender of the insurgents under

Andreas Pico. We also knew that General R. B. Mason had been ordered to California; that

Colonel John D. Stevenson was coming out to California with a regiment of New York

Volunteers; that Commodore Shubrick had orders also from the Navy Department to

control matters afloat; that General Kearny, by virtue of his rank, had the right to control all

the land-forces in the service of the United States; and that Frémont claimed

the same right by virtue of a letter he had received from Colonel Benton, then a Senator,

and a man of great influence with Polk’s Administration. So that among the younger

officers the query was very natural, “Who the devil is Governor of California?”

was soon joined there by Frémont, and they jointly received thewas soon joined

there by Frémont, and they jointly received the surrender of the insurgents under

Andreas Pico. We also knew that General R. B. Mason had been ordered to California; that

Colonel John D. Stevenson was coming out to California with a regiment of New York

Volunteers; that Commodore Shubrick had orders also from the Navy Department to

control matters afloat; that General Kearny, by virtue of his rank, had the right to control all

the land-forces in the service of the United States; and that Frémont claimed

the same right by virtue of a letter he had received from Colonel Benton, then a Senator,

and a man of great influence with Polk’s Administration. So that among the younger

officers the query was very natural, “Who the devil is Governor of California?”

One day I

was on board the Independence frigate, dining with the

ward-room officers, when a

war-vessel was reported in the offing, which in due time was made out to be the

Cyane, Captain DuPont. After dinner, we were all on deck, to watch the new arrival, the

ships meanwhile exchanging signals, which were interpreted that General Kearny was on

board. As the Cyane approached, a boat was sent to meet her, with Commodore

Shubrick’s flag-officer, Lieutenant Lewis, to carry the usual messages, and to invite

General Kearny to come on board the Independence as the guest of Commodore Shubrick.

Quite a number of officers were on deck, among them Lieutenants Wise, Montgomery

Lewis, William Chapman, and others, noted wits and wags of the navy. In due time the

Cyane anchored close by, and our boat was seen returning with a stranger in the

stern-sheets, clothed in army-blue. As the boat came nearer, we saw that it was

General Kearny with an old dragoon coat on, and an army-cap, to which the general

had added the broad visor, cut from a full-dress hat, to shade his face and

eyes against the glaring sun of the Gila region. Chapman exclaimed: “Fellows, the problem

is solved; there is the grand-vizier (visor) by G–d! He is Governor of

California."

All hands received the general with great heartiness, and he soon passed

out of our sight into the commodore’s cabin. Between Commodore Shubrick and General

Kearny existed from that time forward the greatest harmony and good feeling, and no

further trouble existed as to the controlling power on the Pacific coast. General Kearny had

dispatched from San Diego his quartermaster, Colonel Swords, to the Sandwich Islands, to

purchase clothing and stores for his men, and had come up to Monterey, bringing with him

Turner and Warner, leaving Emory and the company of dragoons below. He was delighted

to find a full strong company of artillery, subject to his orders, well supplied with clothing

and money in all respects, and, much to the disgust of our Captain Tompkins, he took half

of his company clothing and part of the money held by me for the relief of his

worn-out and almost naked dragoons left behind at Los Angeles. In a few days he moved

on shore, took up his quarters at Larkin’s house, and established his head-quarters,

with Captain Turner as his adjutant-general. One day Turner and Warner were at my

tent, and, seeing a store-box full of socks, drawers, and calico shirts, of which I

had laid in a three years’ supply, and of which they had none, made known to me their

wants, and I told them to help themselves, which Turner and Warner did. The latter,

however, insisted on paying me the cost, and from that date to this Turner and I have been

close friends. Warner, poor fellow, was afterward killed by Indians. Things gradually

came into shape, a semi-monthly courier line was established from Yerba Buena to

San Diego, and we were thus enabled to keep pace with events throughout the country. In

March Stevenson’s

All hands received the general with great heartiness, and he soon passed

out of our sight into the commodore’s cabin. Between Commodore Shubrick and General

Kearny existed from that time forward the greatest harmony and good feeling, and no

further trouble existed as to the controlling power on the Pacific coast. General Kearny had

dispatched from San Diego his quartermaster, Colonel Swords, to the Sandwich Islands, to

purchase clothing and stores for his men, and had come up to Monterey, bringing with him

Turner and Warner, leaving Emory and the company of dragoons below. He was delighted

to find a full strong company of artillery, subject to his orders, well supplied with clothing

and money in all respects, and, much to the disgust of our Captain Tompkins, he took half

of his company clothing and part of the money held by me for the relief of his

worn-out and almost naked dragoons left behind at Los Angeles. In a few days he moved

on shore, took up his quarters at Larkin’s house, and established his head-quarters,

with Captain Turner as his adjutant-general. One day Turner and Warner were at my

tent, and, seeing a store-box full of socks, drawers, and calico shirts, of which I

had laid in a three years’ supply, and of which they had none, made known to me their

wants, and I told them to help themselves, which Turner and Warner did. The latter,

however, insisted on paying me the cost, and from that date to this Turner and I have been

close friends. Warner, poor fellow, was afterward killed by Indians. Things gradually

came into shape, a semi-monthly courier line was established from Yerba Buena to

San Diego, and we were thus enabled to keep pace with events throughout the country. In

March Stevenson’s  regiment arrived. Colonel Mason also arrived by sea from Callao in the

store-ship Erie, and P. St. George Cooke’s battalion of Mormons reached San Luis

Rey. A. J. Smith and George Stoneman were with him, and were assigned to the company

of dragoons at Los Angeles. All these troops and the navy regarded General Kearny as the

rightful commander, though Frémont still remained at Los Angeles, styling himself

as Governor, issuing orders and holding his battalion of California Volunteers in apparent

defiance of General Kearny. Colonel Mason and Major Turner were sent down by sea with

a pay-master, with muster-rolls and orders to muster this battalion into the

service of the United States, to pay and then to muster them out; but on their reaching Los

Angeles Frémont would not consent to it, and the controversy became so angry that

a challenge was believed to have passed between Mason and Frémont, but the duel

never came about. Turner rode up by land in four or five days, and Frémont,

becoming alarmed, followed him, as we supposed, to over-take him, but he did not

succeed. On Frémont’s arrival at Monterey, he camped in a tent about a mile out of

town and called on General Kearny, and it was reported that the latter threatened him very

severely and ordered him back to Los Angeles immediately, to disband his volunteers, and

to cease the exercise of authority of any kind in the country. Feeling a natural curiosity to

see Frémont, who was then quite famous by reason of his recent explorations and

the still more recent conflicts with Kearny and Mason, I rode out to his camp, and found

him in a conical tent with one Captain Owens, who was a mountaineer, trapper, etc., but

originally from Zanesville, Ohio. regiment arrived. Colonel Mason also arrived by sea from Callao in the

store-ship Erie, and P. St. George Cooke’s battalion of Mormons reached San Luis

Rey. A. J. Smith and George Stoneman were with him, and were assigned to the company

of dragoons at Los Angeles. All these troops and the navy regarded General Kearny as the

rightful commander, though Frémont still remained at Los Angeles, styling himself

as Governor, issuing orders and holding his battalion of California Volunteers in apparent

defiance of General Kearny. Colonel Mason and Major Turner were sent down by sea with

a pay-master, with muster-rolls and orders to muster this battalion into the

service of the United States, to pay and then to muster them out; but on their reaching Los

Angeles Frémont would not consent to it, and the controversy became so angry that

a challenge was believed to have passed between Mason and Frémont, but the duel

never came about. Turner rode up by land in four or five days, and Frémont,

becoming alarmed, followed him, as we supposed, to over-take him, but he did not

succeed. On Frémont’s arrival at Monterey, he camped in a tent about a mile out of

town and called on General Kearny, and it was reported that the latter threatened him very

severely and ordered him back to Los Angeles immediately, to disband his volunteers, and

to cease the exercise of authority of any kind in the country. Feeling a natural curiosity to

see Frémont, who was then quite famous by reason of his recent explorations and

the still more recent conflicts with Kearny and Mason, I rode out to his camp, and found

him in a conical tent with one Captain Owens, who was a mountaineer, trapper, etc., but

originally from Zanesville, Ohio.

I spent an hour or so with Frémont in his tent,

took some tea with him, and left, without being much impressed with him. In due time

Colonel Swords returned from the Sandwich Islands and relieved me as quartermaster.

Captain William G. Marcy, son of the Secretary of War, had also come out in one of

Stevenson’s ships as an assistant commissary of subsistence, and was stationed at

Monterey and relieved me as commissary, so that I reverted to the condition of a

company-officer. While acting as a staff-officer I had lived at the custom-house

in Monterey, but when relieved I took a tent in line with the other company-officers

on the hill, where we had a mess.

Stevenson’s regiment reached San

Francisco Bay early in March, 1847. Three companies were stationed at the Presidio under

Major James A. Hardie; one company (Brackett’s) at Sonoma; three, under Colonel

Stevenson, at Monterey; and three, under Lieutenant-Colonel Burton, at Santa

Barbara. One day I was down at the headquarters at Larkin’s house, when General Kearny

remarked to me that he was going down to Los Angeles in the ship Lexington, and wanted

me to go along as his aide. Of course this was most agreeable to me. Two of Stevenson’s

companies, with the headquarters and the colonel, were to go also. They embarked, and

early in May we sailed for San Pedro. Before embarking, the United States

line-of-battle-ship Columbus had reached the coast from China with Commodore

Biddle, whose rank gave him the supreme command of the navy on the coast. He was busy

in calling in–“lassooing”–from the

land-service the

various naval officers who under Stockton had been doing all sorts of military and civil

service on shore. Knowing that I was to go down the coast with General Kearny, he sent

for me and handed me two unsealed parcels addressed to Lieutenant Wilson, United States

Navy, and Major Gillespie, United States Marines, at Los Angeles. These were written

orders pretty much in these words: “On receipt of this order you will repair at once on

board the United States ship Lexington at San Pedro, and on reaching Monterey you will

report to the undersigned.–JAMES BIDDLE.” Of course, I executed my part

to the letter, and these officers were duly “lassooed.” We sailed down the coast with a fair

wind, and anchored inside the kelp, abreast of Johnson’s house. Messages were forthwith

dispatched up to Los Angeles, twenty miles off, and preparations for horses made for us to

ride up. We landed, and, as Kearny held to my arm in ascending the steep path up the

bluff, he remarked to himself, rather than to me, that it was strange that Frémont

did not want to return north by the Lexington on account of

sea-sickness, but

preferred to go by land over five hundred miles. The younger officers had been discussing

what the general would do with Frémont, who was supposed to be in a state of

mutiny. Some thought he would be tried and shot, some that he would be carried back

in irons; and all agreed that if any one else than Frémont had put on such

airs, and had acted as he had done, Kearny would have shown him no mercy, for he was

regarded as the strictest sort of a disciplinarian. We had a pleasant ride across the plain

which lies between the sea-shore and Los Angeles, which we reached in about three

hours, the infantry following on foot. We found Colonel P. St. George Cooke living at the

house of a Mr. Pryor, and the company of dragoons, with A. J. Smith, Davidson,

Stoneman, and Dr. Griffin, quartered in an adobe-house close by. Frémont

held his court in the only two-story frame-house in the place. After some time

spent at Pryor’s house, General Kearny ordered me to call on Frémont to notify

him of his arrival, and that he desired to see him. I walked round to the house which had

been pointed out to me as his, inquired of a man at the door if the colonel was in, was

answered “Yes,” and was conducted to a large room on the second floor, where very soon

Frémont came in, and I delivered my message. As I was on the point of leaving, he

inquired where I was going to, and I answered that I was going back to Pryor’s house,

where the general was, when he remarked that if I would wait a moment he would go

along. Of course I waited, and he soon joined me, dressed much as a Californian, with the

peculiar high, broad-brimmed hat, with a fancy cord, and we walked together back

to Pryor’s, where I left him with General Kearny. We spent several days very pleasantly at

Los Angeles, then, as now, the chief pueblo of the south, famous for its grapes,

fruits, and wines. There was a hill close to the town, from which we had a perfect view of

the place. The surrounding country is level, utterly devoid of trees, except the willows and

cotton-woods that line the Los Angeles Creek and the acequias, or ditches,

which lead from it. The space of ground cultivated in vineyards seemed about five miles by

one, embracing the town. Every house had its inclosure of vineyard, which resembled a

miniature orchard, the vines being very old, ranged in rows, trimmed very close, with

irrigating ditches so arranged that a stream of water could be diverted between each row of

vines. The Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers are fed by melting snows from a range of

mountains to the east, and the quantity of cultivated lands depends upon the amount of

water. This did not seem to be very large; but the San Gabriel River, close by, was

represented to contain a larger volume of water, affording the means of greatly enlarging

the space for cultivation. The climate was so moderate that oranges, figs, pomegranates,

etc., were generally to be found in every yard or inclosure.

Stevenson’s regiment reached San

Francisco Bay early in March, 1847. Three companies were stationed at the Presidio under

Major James A. Hardie; one company (Brackett’s) at Sonoma; three, under Colonel

Stevenson, at Monterey; and three, under Lieutenant-Colonel Burton, at Santa

Barbara. One day I was down at the headquarters at Larkin’s house, when General Kearny

remarked to me that he was going down to Los Angeles in the ship Lexington, and wanted

me to go along as his aide. Of course this was most agreeable to me. Two of Stevenson’s

companies, with the headquarters and the colonel, were to go also. They embarked, and

early in May we sailed for San Pedro. Before embarking, the United States

line-of-battle-ship Columbus had reached the coast from China with Commodore

Biddle, whose rank gave him the supreme command of the navy on the coast. He was busy

in calling in–“lassooing”–from the

land-service the

various naval officers who under Stockton had been doing all sorts of military and civil

service on shore. Knowing that I was to go down the coast with General Kearny, he sent

for me and handed me two unsealed parcels addressed to Lieutenant Wilson, United States

Navy, and Major Gillespie, United States Marines, at Los Angeles. These were written

orders pretty much in these words: “On receipt of this order you will repair at once on

board the United States ship Lexington at San Pedro, and on reaching Monterey you will

report to the undersigned.–JAMES BIDDLE.” Of course, I executed my part

to the letter, and these officers were duly “lassooed.” We sailed down the coast with a fair

wind, and anchored inside the kelp, abreast of Johnson’s house. Messages were forthwith

dispatched up to Los Angeles, twenty miles off, and preparations for horses made for us to

ride up. We landed, and, as Kearny held to my arm in ascending the steep path up the

bluff, he remarked to himself, rather than to me, that it was strange that Frémont

did not want to return north by the Lexington on account of

sea-sickness, but

preferred to go by land over five hundred miles. The younger officers had been discussing

what the general would do with Frémont, who was supposed to be in a state of

mutiny. Some thought he would be tried and shot, some that he would be carried back

in irons; and all agreed that if any one else than Frémont had put on such

airs, and had acted as he had done, Kearny would have shown him no mercy, for he was

regarded as the strictest sort of a disciplinarian. We had a pleasant ride across the plain

which lies between the sea-shore and Los Angeles, which we reached in about three

hours, the infantry following on foot. We found Colonel P. St. George Cooke living at the

house of a Mr. Pryor, and the company of dragoons, with A. J. Smith, Davidson,

Stoneman, and Dr. Griffin, quartered in an adobe-house close by. Frémont

held his court in the only two-story frame-house in the place. After some time

spent at Pryor’s house, General Kearny ordered me to call on Frémont to notify

him of his arrival, and that he desired to see him. I walked round to the house which had

been pointed out to me as his, inquired of a man at the door if the colonel was in, was

answered “Yes,” and was conducted to a large room on the second floor, where very soon

Frémont came in, and I delivered my message. As I was on the point of leaving, he

inquired where I was going to, and I answered that I was going back to Pryor’s house,

where the general was, when he remarked that if I would wait a moment he would go

along. Of course I waited, and he soon joined me, dressed much as a Californian, with the

peculiar high, broad-brimmed hat, with a fancy cord, and we walked together back

to Pryor’s, where I left him with General Kearny. We spent several days very pleasantly at

Los Angeles, then, as now, the chief pueblo of the south, famous for its grapes,

fruits, and wines. There was a hill close to the town, from which we had a perfect view of

the place. The surrounding country is level, utterly devoid of trees, except the willows and

cotton-woods that line the Los Angeles Creek and the acequias, or ditches,

which lead from it. The space of ground cultivated in vineyards seemed about five miles by

one, embracing the town. Every house had its inclosure of vineyard, which resembled a

miniature orchard, the vines being very old, ranged in rows, trimmed very close, with

irrigating ditches so arranged that a stream of water could be diverted between each row of

vines. The Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers are fed by melting snows from a range of

mountains to the east, and the quantity of cultivated lands depends upon the amount of

water. This did not seem to be very large; but the San Gabriel River, close by, was

represented to contain a larger volume of water, affording the means of greatly enlarging

the space for cultivation. The climate was so moderate that oranges, figs, pomegranates,

etc., were generally to be found in every yard or inclosure.

At the time of our visit, General Kearny was making his preparations to return

overland to the United States, and he arranged to secure a volunteer escort out of the

battalion of Mormons that was then stationed at San Luis Rey, under Colonel Cooke and a

Major Hunt. This battalion was only enlisted for one year, and the time for their discharge

was approaching, and it was generally understood that the majority of the men wanted to be

discharged so as to join the Mormons who had halted at Salt Lake, but a lieutenant and

about forty men volunteered to return to Missouri as the escort of General Kearny. These

were mounted on mules and horses, and I was appointed to conduct them to Monterey by

land.

Leaving the party at Los Angeles to follow by sea in the Lexington, I started with the

Mormon detachment and traveled by land. We averaged about thirty miles a day, stopped

one day at Santa Barbara, where I saw Colonel Burton, and so on by the usually traveled

road to Monterey, reaching it in about fifteen days, arriving some days in advance of the

Lexington.

Continue to Part II of Sherman’s Early California

Story

Return to the top of the page.

|