Early

History of California

Early

History of California

Early

History of San Francisco

“Ranch

and Mission Days in Alta California,” by Guadalupe Vallejo

“Life

in California Before the Gold Discovery,” by John Bidwell

William

T. Sherman and Early Calif. History

William

T. Sherman and the Gold Rush

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1846 - 1849

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1850 - 1851

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1852 - 1854

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1855 - 1856

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1857 - 1861

California

Gold Rush Chronology 1862 - 1865

An

Eyewitness to the Gold Discovery

Military

Governor Mason’s Report on the Discovery of Gold

A

Rush to the Gold Washings — From the California Star

The

Discovery — as Viewed in New York and London

Steamer

Day in the 1850s

Sam

Brannan Opens New Bank - 1857

|

But

I still had it in my mind to try to find gold; so early in the spring of

1845 I made it a point to visit the mines in the south discovered by Ruelle

in 1841, They were in the mountains about twenty miles north or north-east

of the Mission of San Fernando, or say fifty miles from Los Angeles. I

wanted to see the Mexicans working there, and to gain what knowledge I

could of gold digging. Dr. John Townsend went with me. Pablo’s confidence

that there was gold on Bear River was fresh in my mind; and I hoped the

same year to find time to return there and explore, and if possible find

gold in the Sierra Nevada. But I had no time that busy year to carry out

my purpose. The Mexicans’ slow and inefficient manner of working the mine

was most discouraging. When I returned to Sutter’s Fort the same spring,

Sutter desired me to engage with him for a year as bookkeeper, which meant

his general business man as well. His financial matters being in a bad

way, I consented. I had a great deal to do besides keeping the books. Among

other undertakings we sent men southeast in the Sierra Nevada about forty

miles from the fort to saw lumber with a whipsaw. Two men would saw of

good timber about one hundred or one hundred and twenty-five feet

a day. Early in July I framed an excuse to go to the mountains to give

the men some special directions about lumber needed at the fort. The day

was one of the hottest I had ever experienced. No place looked favorable

for a gold discovery. I even attempted to descend into a deep gorge through

which meandered a small stream, but gave it up on account of the brush

and the heat. My search was fruitless. The place where Marshall discovered

gold in 1848 was about forty miles to the north of the saw-pits at

this place. The next spring, 1849, I joined a party to go to the mines

on the south of the Consumne and Mokelumne rivers. The first day we reached

a trading post — Digg’s, I think, was the name. Several traders had

there pitched their tents to sell goods. One of them was Tom Fallon, whom

I knew. This post was within a few miles of where Sutter’s men sawed the

lumber in 1845. I asked Fallon if he had ever seen the old saw-pits

where Sicard and Dupas had worked in 1845. He said he had, and knew the

place well. Then I told him how I had attempted that year to descend into

the deep gorge to the south of it to look for gold.

“My

stars!” he said. “Why, that gulch down there was one of the richest

placers that have ever been found in this country”; and he told me

of men who had taken out a pint cupful of nuggets before breakfast.

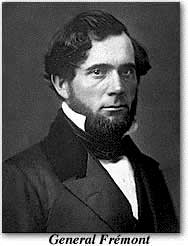

Fremont’s

first visit to California was in the month of March, 1844. He came via

eastern Oregon, traveling south, and passing east of the Sierra Nevada,

and crossed the chain about opposite the bay of San Francisco, at the head

of the American River, and descended into the Sacramento Valley to Sutter’s

Fort. It was there I first met him. He staid but a short time, three or

four weeks perhaps, to refit with fresh mules and horses and such provisions

as he could obtain, and then set out on his return to the United States.

Coloma, where Marshall afterward discovered gold, was on one of the branches

of the American River. Fremont probably came down that very stream. How

strange that he and his scientific corps did not discover signs of gold,

as Commodore Wilkes’s party had done when coming overland from Oregon in

1841! One morning at the breakfast table at Sutter’s, Fremont was urged

to remain a while and go to the coast, and among other things which it

would be of interest for him to see was mentioned a very large redwood

tree (Sequoia sempervirens) near Santa Cruz, or rather a cluster of trees,

forming apparently a single trunk, which was said to be seventy-two

feet in circumference. I then told Fremont of the big tree I had seen in

the Sierra Nevada in October, 1841, which I afterwards verified to be one

of the fallen big trees of the Calaveras Grove. I therefore believe myself

to have been the first white man to see the mammoth trees of California.

The Sequoia are found no where except in California. The redwood that I

speak of is the Sequoia sempervirens, and is confined to the sea-coast

and the west side of the Coast Range Mountains. the Sequoia gigantea, or

mammoth tree, is found only on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada —

nowhere farther north than latitude 38” 30’. Fremont’s

first visit to California was in the month of March, 1844. He came via

eastern Oregon, traveling south, and passing east of the Sierra Nevada,

and crossed the chain about opposite the bay of San Francisco, at the head

of the American River, and descended into the Sacramento Valley to Sutter’s

Fort. It was there I first met him. He staid but a short time, three or

four weeks perhaps, to refit with fresh mules and horses and such provisions

as he could obtain, and then set out on his return to the United States.

Coloma, where Marshall afterward discovered gold, was on one of the branches

of the American River. Fremont probably came down that very stream. How

strange that he and his scientific corps did not discover signs of gold,

as Commodore Wilkes’s party had done when coming overland from Oregon in

1841! One morning at the breakfast table at Sutter’s, Fremont was urged

to remain a while and go to the coast, and among other things which it

would be of interest for him to see was mentioned a very large redwood

tree (Sequoia sempervirens) near Santa Cruz, or rather a cluster of trees,

forming apparently a single trunk, which was said to be seventy-two

feet in circumference. I then told Fremont of the big tree I had seen in

the Sierra Nevada in October, 1841, which I afterwards verified to be one

of the fallen big trees of the Calaveras Grove. I therefore believe myself

to have been the first white man to see the mammoth trees of California.

The Sequoia are found no where except in California. The redwood that I

speak of is the Sequoia sempervirens, and is confined to the sea-coast

and the west side of the Coast Range Mountains. the Sequoia gigantea, or

mammoth tree, is found only on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada —

nowhere farther north than latitude 38” 30’.

Sutter’s

Fort was an important point from the very beginning of the colony. The

building of the fort and all subsequent immigration added to its importance,

for that was the first point of destination to those who came by way of

Oregon or direct across the plains. The fort was begun in 1842 and finished

in 1844. There was no town till after the gold discovery in 1848, when

it became the bustling, buzzing center for merchants, traders, miners,

etc., and every available room was in demand. In 1849 Sacramento City was

laid off on the river two miles west of the fort, and the town grew up

there at once into a city. The first town was laid off by Hastings and

myself in the month of January, 1846, — about three or four miles below

the mouth of the American River, and called Sutterville. But first the

Mexican war, then the lull which always follows excitement, and then the

rush and roar of the gold discovery prevented its building up till it was

too late. Attempts were several times made to revive Sutterville, but Sacramento

City had become too strong to be removed. Sutter always called his colony

and fort “New Helvetia,” in spite of which the name mostly used

by others, before the Mexican war, was Sutter’s Fort, or Sacramento, and

later Sacramento altogether.

Sutter’s

many enterprises continued to create a growing demand for lumber. Every

year, and sometimes more than once, he sent parties into the mountains

to explore for an available site to build a sawmill on the Sacramento River

or some of its tributaries, by which the lumber could be rafted down to

the fort. There was no want of timber or of water power in the mountains,

but the canyon features of the streams rendered rafting impracticable.

The year after the war (1847) Sutter’s needs for lumber were even greater

than ever, although his embarrassments had increased and his ability to

undertake new enterprises became less and less. Yet, never discouraged,

nothing daunted, another hunt must be made for a sawmill site. This time

Marshall happened to be the man chosen by Sutter  to

search the mountains. He was gone about a month, and returned with a most

favorable report. James W. Marshall went across the plains to Oregon in

1844, and thence came to California the next year. He was a wheelwright

by trade, but, being very ingenious, he could turn his hand to almost anything.

So he acted as carpenter for Sutter, and did many other things, among which

I may mention making wheels for spinning wool, and looms, reeds, and shuttles

for weaving yarn into coarse blankets for the Indians, who did the carding,

spinning, weaving, and all other labor. In 1846 Marshall went through the

war to its close as a private. Besides his ingenuity as a mechanic, he

had most singular traits. Almost everyone pronounced him half crazy or

hare-brained. He was certainly eccentric, and perhaps somewhat flighty.

His insanity, however, if he had any, was of a harmless kind; he was neither

vicious nor quarrelsome. He had great, almost overweening, confidence in

his ability to do anything as a mechanic. I wrote the contract between

Sutter and him to build the mill. Sutter was to furnish the means; Marshall

was to build and run the mill, and have a share of the lumber for his compensation.

His idea was to haul the lumber part way and raft it down the American

River to Sacramento, and thence, his part of it, down the Sacramento River

and through Suisun and San Pablo bays to San Francisco for a market. Marshall’s

mind, in some respects at least, must have been unbalanced. It is hard

to conceive how any sane man could have been so wide of the mark, or how

any one could have selected such a site for a saw-mill under the circumstances.

Surely no other man than Marshall ever entertained so wild a scheme as

that of rafting sawed lumber down the canyons of the American River, and

no other man than Sutter would have been so confiding and credulous as

to patronize him. It is proper to say that, under great difficulties, enhanced

by winter rains, Marshall succeeded in building the mill — a very good

one, too, of the kind. It had improvements which I had never seen in sawmills,

and I had had considerable experience in Ohio. But the mill would not run

because the wheel was planed too low. It was an old-fashioned flutter

wheel that propelled an upright saw. The gravelly bar below the mill backed

the water up, and submerged and stopped the wheel. The remedy was to dig

a channel or tail-race through the bar below to conduct away the water.

The wild Indians of the mountains were employed to do the digging. Once

through the bar there would be plenty of fall. The digging was hard and

took some weeks. As soon as the water began to run through the tail-race

the wheel was blocked, the gate raised, and the water permitted to gush

through all night. It was Marshall’s custom to examine the race while the

water was running through in the morning, so as to direct the Indians where

to deepen it, and then shut off the water for them to work during the day.

The water was clear as crystal, and the current was swift enough to sweep

away the sand and lighter materials. Marshall made these examinations early

in the morning while the Indians were getting their breakfast. It was on

one of these occasions, in the clear shallow water, that be saw something

bright and yellow. He picked it up — it was a piece of gold! The world

has seen and felt the result. The mill sawed little or no lumber; as a

lumber enterprise the project was a failure, but as a gold discovery it

was a grand success. There was no excitement at first, nor for three or

four months — because the mine was not known to be rich, or to exist

anywhere except at the sawmill, or to be available to any one except Sutter,

to whom every one conceded that it belonged. to

search the mountains. He was gone about a month, and returned with a most

favorable report. James W. Marshall went across the plains to Oregon in

1844, and thence came to California the next year. He was a wheelwright

by trade, but, being very ingenious, he could turn his hand to almost anything.

So he acted as carpenter for Sutter, and did many other things, among which

I may mention making wheels for spinning wool, and looms, reeds, and shuttles

for weaving yarn into coarse blankets for the Indians, who did the carding,

spinning, weaving, and all other labor. In 1846 Marshall went through the

war to its close as a private. Besides his ingenuity as a mechanic, he

had most singular traits. Almost everyone pronounced him half crazy or

hare-brained. He was certainly eccentric, and perhaps somewhat flighty.

His insanity, however, if he had any, was of a harmless kind; he was neither

vicious nor quarrelsome. He had great, almost overweening, confidence in

his ability to do anything as a mechanic. I wrote the contract between

Sutter and him to build the mill. Sutter was to furnish the means; Marshall

was to build and run the mill, and have a share of the lumber for his compensation.

His idea was to haul the lumber part way and raft it down the American

River to Sacramento, and thence, his part of it, down the Sacramento River

and through Suisun and San Pablo bays to San Francisco for a market. Marshall’s

mind, in some respects at least, must have been unbalanced. It is hard

to conceive how any sane man could have been so wide of the mark, or how

any one could have selected such a site for a saw-mill under the circumstances.

Surely no other man than Marshall ever entertained so wild a scheme as

that of rafting sawed lumber down the canyons of the American River, and

no other man than Sutter would have been so confiding and credulous as

to patronize him. It is proper to say that, under great difficulties, enhanced

by winter rains, Marshall succeeded in building the mill — a very good

one, too, of the kind. It had improvements which I had never seen in sawmills,

and I had had considerable experience in Ohio. But the mill would not run

because the wheel was planed too low. It was an old-fashioned flutter

wheel that propelled an upright saw. The gravelly bar below the mill backed

the water up, and submerged and stopped the wheel. The remedy was to dig

a channel or tail-race through the bar below to conduct away the water.

The wild Indians of the mountains were employed to do the digging. Once

through the bar there would be plenty of fall. The digging was hard and

took some weeks. As soon as the water began to run through the tail-race

the wheel was blocked, the gate raised, and the water permitted to gush

through all night. It was Marshall’s custom to examine the race while the

water was running through in the morning, so as to direct the Indians where

to deepen it, and then shut off the water for them to work during the day.

The water was clear as crystal, and the current was swift enough to sweep

away the sand and lighter materials. Marshall made these examinations early

in the morning while the Indians were getting their breakfast. It was on

one of these occasions, in the clear shallow water, that be saw something

bright and yellow. He picked it up — it was a piece of gold! The world

has seen and felt the result. The mill sawed little or no lumber; as a

lumber enterprise the project was a failure, but as a gold discovery it

was a grand success. There was no excitement at first, nor for three or

four months — because the mine was not known to be rich, or to exist

anywhere except at the sawmill, or to be available to any one except Sutter,

to whom every one conceded that it belonged.  Time

does not permit me to relate how I carried the news of the discovery to

San Francisco; how the same year I discovered gold on Feather River and

worked it; how I made the first weights and scales to weigh the first gold

for Sam Brannan; how the richness of the mines became known by the Mormons

who were employed by Sutter to work at the sawmill, working about on Sundays

and finding it in the crevices along the stream and taking it to Brannan’s

store at the fort, and how Brannan kept the gold a secret as long as he

could till the excitement burst out all at once like wildfire. Time

does not permit me to relate how I carried the news of the discovery to

San Francisco; how the same year I discovered gold on Feather River and

worked it; how I made the first weights and scales to weigh the first gold

for Sam Brannan; how the richness of the mines became known by the Mormons

who were employed by Sutter to work at the sawmill, working about on Sundays

and finding it in the crevices along the stream and taking it to Brannan’s

store at the fort, and how Brannan kept the gold a secret as long as he

could till the excitement burst out all at once like wildfire.

Among the

notable arrivals at Sutter’s Fort should be mentioned that of Castro and

Castillero, in the fall of 1845. The latter had been before in California,

sent, as he had been this time, as a peace commissioner from Mexico. Castro

was so jealous that it was impossible for Sutter to have anything like

a private interview with him. Sutter, however, was given to understand

that, as he had stood friendly to Governor Micheltorena on the side of

Mexico in the late troubles, he might rely on the friendship of Mexico,

to which he was enjoined to continue faithful in all emergencies. Within

a week Castillero was shown at San José a singular heavy reddish

rock, which had long been known to the Indians, who rubbed it on their

bands and faces to paint them. The Californians had often tried to smelt

this rock, in a blacksmith’s fire, thinking it to be silver or some other

precious metal. But Castillero, who was an intelligent man and a native

of Spain, at once recognized it as quicksilver, and noted its resemblance

to the cinnabar in the mines of Almaden. A company was immediately formed

to work it, of which Castillero, Castro, Alexander Forbes, and others were

members. The discovery of quicksilver at this time seems providential in

view of its absolute necessity to supplement the imminent discovery of

gold, which stirred and waked into new life the industries of the world.

It is a

question whether the United States could have stood the shock of the great

rebellion of 1861 had the California gold discovery not been made. Bankers

and business men of New York in 1864 did not hesitate to admit that but

for the gold of California, which monthly poured its five or six millions

into that financial center, the bottom would have dropped out of everything,

These timely arrivals so strengthened the nerves of trade and stimulated

business as to enable the Government to sell its bonds at a time when its

credit was its life-blood and the main reliance by which to feed,

clothe, and maintain its armies. Once our bonds went down to thirty-eight

cents on the dollar. California gold averted a total collapse, and enabled

a preserved Union to come forth from the great conflict with only four

billions of debt instead of a hundred billions. The hand of Providence

so plainly seen in the discovery of gold is no less manifest in the time

chosen for its accomplishment.

I must reserve

for itself in a concluding paper my personal recollections of Fremont’s

second visit to California in 1845-46, which I have purposely wholly

omitted here. It was most important, resulting as it did in the acquisition

of that territory by the United States.

John Bidwell.

Return to the top of the page.

|