Chinese in San

Francisco

Chinese in San

Francisco

California Gold Rush

|

THE CHINESE

by Henry Kittredge Norton

Like every other nation in the world, the Chinese Empire was represented

in the great rush for California which took place during the gold excitement.

At the beginning of the year 1849 there were in the state only fifty-four

Chinamen. At the news of the gold discovery a steady immigration commenced

which continued until 1876, at which time the Chinese in the United States

numbered 151,000 of whom 116,000 were in the state of California. This

increase in their numbers, rapid even in comparison with the general increase

in population, was largely due to the fact that previous to the year 1869

China was nearer to the shores of California than was the eastern portion

of the United States. Another circumstance which contributed to the heavy

influx of Chinese was the fact that news of the gold discovery found southeastern

China in poverty and ruin caused by the Taiping rebellion. Masters of vessels

made the most of this coincidence of favorable circumstances. They distributed

in all the Chinese ports, placards, maps and pamphlets with highly colored

accounts of the golden hills of California. The fever spread among the

yellow men as it did among others, and the ship-men reaped a harvest

from passage money.

Probably the most conspicuous characteristic of the Chinese is their

passion for work. The Chinaman seemingly must work. If he cannot secure

work at a high wage he will take it at a low wage, but he is a good bargainer

for his labor and only needs the opportunity to ask for more pay. This

is true of the whole nation, from the lowest to the highest. They lack

inventiveness and initiative but have an enormous capacity for imitation.

With proper instruction their industrial adaptability is very great. They

learn what they are shown with almost incredible facility, and soon become

adept.

If the social conditions prevailing in California in the days of ’49

are recalled, it is not difficult to realize how welcome were the Chinese

who first came to the country. Here were men who would do the drudgery

of life at a reasonable wage when every other man had but one idea—to

work at the mines for gold. Here were cooks, laundrymen, and servants ready

and willing. Just what early California civilization most wanted these

men could and would supply.

The result was that the Chinaman was welcomed; he was considered quite indispensable. He was in demand as a laborer, as a carpenter, as a cook; the restaurants which he established were well patronized; his agricultural

endeavors in draining and tilling the rich tule lands were praised. Governor

McDougal referred to him as “one of the most worthy of our newly adopted

citizens.” In public functions he was given a place of honor, for

the Californians of those days appreciated the touch of color which he

gave to the life of the country. The Chinese took a prominent part in the

parades in celebration of the admission of the state to the Union. The

Alta California, a San Francisco newspaper, went so far as to say,

“The China Boys will yet vote at the same polls, study at the same

schools, and bow at the same altar as our countrymen.” Their cleanliness,

unobtrusiveness and industry were everywhere praised.

The Chinese were surely in a land of milk and honey. They had left

a land of war and starvation where work could not be had and food must

be begged and here they found themselves in the midst of work and plenty.

They were everywhere welcomed and their wages were such that they could

save a substantial part to send back to the families they had left at home

in China; or, if they did not wish to labor for masters, they could go

to the mines. Here they could take an old claim which had been abandoned

by the white miner and dig from it gold dust which to them represented

wealth untold. They were careful not to antagonise these whites by prospecting

ahead of them, and in return they received the same treatment in the mining

districts that they had met with in San Francisco.

The Chinaman was welcomed as long as the surface gold was plentiful

enough to make rich all who came. But that happy situation was not long

to continue. Thousands of Americans came flocking in to the mines. Rich

surface claims soon became exhausted. These newcomers did not find it so

easy as their predecessors had done to amass large fortunes in a few days.

California did not fulfil the promise of the golden tales that had been

told of her. These gold-seekers were disappointed. In the bitterness

of their disappointment they turned upon the men of other races who were

working side by side with them and accused them of stealing their wealth.

They boldly asserted that California’s gold belonged to them. The cry of

“California for the Americans” was raised and taken up on all

sides.

Within a short time the Frenchman, the Mexican and the Chileño

had been driven out and the full force of this anti-foreign persecution

fell upon the unfortunate Chinaman. From the beginning, though well received,

the Chinese had been a race apart. Their peculiar dress and pigtail marked

them off from the rest of the population. Their camps at the mines were

always apart from the main camps of white miners. This made it the easier

to turn upon them this hatred of outsiders. With the great inrush of gold-seekers

the abandoned claims which the Chinese had been working, again became desirable

to the whites and the Chinese were driven from them with small concern.

Where might made right the peaceable Chinaman had little chance.

The state legislature was wholly in sympathy with the anti-foreign

movement, and as early as 1850 passed the Foreign Miners’ License law.

This imposed a tax of twenty dollars a month on all foreign miners. Instead

of bringing into the state treasury the revenue promised by its framers,

this law had the effect of depopulating some camps and of seriously injuring

all of them. San Francisco became overrun with penniless foreigners and

their care became a serious problem. The law was conceded to be a failure

and was repealed the following year.

By

the time this was done, however, the Chinese had become the most conspicuous

body of foreigners in the country and therefore had to bear the brunt of

the attacks upon the foreign element. Governor Bigler suddenly became inspired

with the realization of the value of an attack upon them as a political

asset. He sent a special message to the legislature in which he charged

them with being contract “coolie” laborers, avaricious, ignorant

of moral obligations, incapable of being assimilated, and dangerous to

the public welfare. The result was a renewal of the foreign miners’ tax,

but in a milder form than its predecessor.

This did not satisfy the miners, who were at that time the strongest

body, in the community, and the next year the tax was again made prohibitive.

But it was not only the miners who hated the Chinese. The yield of

the placers began to decline in 1853-4, and the discovery of gold in Australia

brought on a financial panic in the latter year. Prices, rents and values

fell rapidly and many business houses failed. There were strikes for higher

wages among laborers and mechanics though the prevalent rate for skilled

labor was ten dollars per day and for unskilled three dollars and a half.

Investors became alarmed and, withdrew their capital. Thousands of unsuccessful

miners drifted back into San Francisco and began to look for work at their

old time occupations. The labor market was glutted and an enormous number

were out of work.

To these unemployed men the presence of thousands of Chinese, thrifty,

industrious, cheap, and above all, un-American, was obviously the

cause of their plight. The cry was raised that the large number of Chinese

in the country tended to injure the interests of the working classes and

to degrade labor. It was claimed that they, deprived white men of positions

by taking lower wages and that they sent their savings back to China; that

thus they were human leeches sucking the very life-blood of this country.

Whoever came to their defense was immediately accused of having mercenary

motives or of being half-witted.

The “coolie” fiction of Governor Bigler was seized upon.

In the first half of the nineteenth century a pseudo-slave trade had

sprung up in transporting Chinese laborers under contract to work at a

certain wage for a certain period to Cuba, and parts of South America.

Such laborers were ignorantly called “coolies” by those who were

not familiar with the Chinese language. The word itself comes from two

Chinese words, “koo” meaning to rent, and “lee” meaning

muscle. The coolies are those who rent out their muscles, that is, unskilled

laborers. In the four classes of China they rank with the third, being

considered a higher class than the merchants but below the scholars and

farmers. The word in no way signifies any sort of bondage. The “coolies”

are perfectly free just as our own laborers are.

The Chinese who came to California were largely of this class and so

described themselves on their arrival. It did not take long for the anti-Chinese

agitators to define a “coolie” as a contract laborer and to describe

how he was bound to a master in China to work a certain number of years

at a small wage and how this terrible system was eating the very vitals

out of American labor. This American labor about which there was so much

concern was almost wholly composed of Irish and other European aliens who

were no more American than the Chinese. But they had a vote in prospect.

The Chinese did not.

While the success of the coolie fiction was largely due to the fact

that there were so many who wanted to believe it, a number of circumstances

combined to give it greater vitality. Most of the business transactions

of the Chinese were done through their benevolent organizations which came

to be locally known as the “Six Companies.” The Companies often

contracted for large bodies of laborers and this fact led the unthinking

to conclude that these laborers were under contract with the Six Companies

to work for them as they should direct. This was not the true situation.

These Companies simply acted as clearing-houses for all sorts of transactions

among the Chinese, as they had found that they could handle things in a

strange land more satisfactorily through such associations than they could

individually.

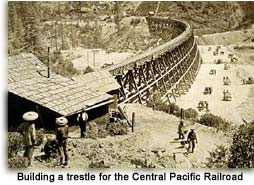

Another thing which strengthened the coolie fiction was the manner

in which the Chinese were employed on the construction work. of the Central

Pacific Railroad. Because of the scarcity of labor the men in charge of

this construction work had sent an agent to China to secure Chinese laborers.

In order to get these men over to this country, it was necessary to advance

their passage-money and other expenses. To cover this loan each Chinaman

so employed signed a promissory note for $75. This note provided for monthly

instalment payments running over a period of seven months and was endorsed

by friends in China. Each laborer was guaranteed a wage of $35 a month.

This financial arrangement was of course seized upon and made much of by

the anti-Chinese agitators as the final proof of “coolieism.”

The belief that the Chinese were contract laborers was one of those

unfortunate errors which sometimes became current in our civic life, and

by frequent repetition receive almost universal acceptance. In the present

instance this phantom of Chinese slavery became so thoroughly a part of

the political life of the Pacific Coast that no attempt was made to reach

the truth of the matter. Every man in public life was under so binding

a necessity to accept the popular belief in regard to the Chinese and to

truckle to it at every turn, that for one to seek the real truth of the

matter was to end forthwith his political career.

In the years following 1854 this unthinking, prejudiced, anti-Chinese

movement ran riot. Various schemes were proposed for ridding the country

of the Chinese as if they were a pest. It was seriously suggested that

they be all returned to China, but as this would have involved an expense

of about seven millions of dollars and ten or a dozen ships for every vessel

that was available, it was reluctantly laid aside. This scheme failing,

it was asserted that they could at least be driven from the mines. But

as this would have deprived the state of a large revenue from licenses

and would have crowded the outcasts in still greater numbers to the cities

and agricultural districts, this too was abandoned.

Various local authorities passed legislation intended to harass them.

Most of the Chinese were in San Francisco, so the principal efforts were

made in that city, The famous “pig-tail ordinance” required

all convicted male prisoners to have their hair cut within one inch of

their heads. This particular piece of idiocy was vetoed by the mayor but

others almost as vicious were passed.

Many of these were declared unconstitutional by the courts, but even

the courts were not at all times consistent friends of the Chinaman. The

worst blow which they received was embodied in a decision given by the

Chief Justice of the state Supreme Court. There was a statute on the books

which prohibited “negroes and Indians” from testifying against

a white man in the courts of the state. The court held, in a brilliantly

logical opinion, that this included the Chinese for the reason that in

the days of Columbus all of the countries washed by Chinese waters had

been called “Indian.”

During the Civil War other issues overshadowed the Chinese question

and the Orientals had a brief respite. But in 1868 the Burlingame treaty

was entered into between the United States and China. It provided for reciprocal

exemption from persecution on account of religious belief, the privilege

of schools and colleges, and in fact it agreed that every Chinese citizen

in the United States should have every privilege which was expected by

the American citizen in China. Though naturalization was especially excepted,

the provisions of this treaty aroused a storm of antagonism on the Pacific

Coast. The labor agitators decried the treaty as a betrayal of the American

workingman, and the whole Chinese question was up again in more violent

form than ever before.

The panic of 1873 and its ill effects brought the matter sharply before

the public and especially that portion of it that was out of work. The

crisis was averted for the time, however, by the opening of the Consolidated

Virginia mines in Nevada and the local wave of prosperity which followed.

But in 1877 the bottom fell out of the whole western business world and

brought back the old agitation with tenfold violence. It was made worse

by the always apparent fact that the Chinese were the last to join the

unemployed. In fact they seldom joined at all. Gardening, farming, laundering,

cooking and housework were almost monopolized by them. The railroads employed

thousands of them and they were engaged to some extent in manufacturing. Virginia mines in Nevada and the local wave of prosperity which followed.

But in 1877 the bottom fell out of the whole western business world and

brought back the old agitation with tenfold violence. It was made worse

by the always apparent fact that the Chinese were the last to join the

unemployed. In fact they seldom joined at all. Gardening, farming, laundering,

cooking and housework were almost monopolized by them. The railroads employed

thousands of them and they were engaged to some extent in manufacturing.

This was more than could be borne by the much-oppressed laboring

man, who claimed that the Chinese, were robbing him of his bread and, which

was worse, the only one who benefitted by their labor was that other arch-enemy

of the laboring man, the capitalist. Something must be done. The courts

had annulled the efforts of their municipal authorities and legislatures

when these had tried to help them; Congress had thrown them but a stone;

the treaty-making power had betrayed them; they must take matters

into their own hands. And this they proceeded to do.

Their method of procedure was in most cases to sack and burn the Chinese

laundries and other commercial establishments operated by the Orientals.

It was left for Los Angeles to furnish the most terrible example of all.

Here nineteen Chinamen were hanged and shot in one evening. The massacre

was accompanied by the theft of over $40,000 worth of their goods.

It was in the south in fact that the violent opposition to the Chinese

had first found strong supporters. Here were many who were accustomed to

assert the “superiority” of their race and to attach the idea

of servitude to all inferior races. To work at all was well-nigh intolerable,

but to work beside a “pig-tail” upon whose wearer even

the wild Indian looked down, was to abasing to be borne. From these southerners

this feeling rapidly spread among the immigrants from the poorer countries

of Europe, who at home were in a position almost of servitude. Arrived

in this country and endowed with the rights of citizenship, for which they

are utterly unfitted, they immediately seek to raise themselves higher

in their own estimation by trampling underfoot the rights of others.

But, beside these prejudices due to race-feeling and ignorance,

there were real causes of discontent against the Chinese. They were not

given to sexual immorality themselves but some of them engaged in the business

of importing women whom they would prostitute to others for gain. Gambling

was an all-prevalent vice. These two features of the Chinese situation

received far more emphasis even among thoughtful people than should have

been given to them. This came about because of the practice of “seeing

Chinatown,” which like “seeing the world” too often meant

seeing the worst possible side of it. The proportion of prostitutes among

the Chinese was little if any higher than among the other races in California

at the time but much publicity spread the idea of great numbers. Gambling,

too, while very generally indulged in by the Chinese, was never among themselves

the vice which was made of it by the Americans who frequented the Chinese

houses. The Chinaman gambled for small stakes as an amusement and never

to his own destruction. But while gambling and immorality have been

over-emphasized,

one charge remains against them in all its original strength. The Chinese

quarter was very unclean. Their cleanly persons and spotless linen were

in strange contrast to their filthy homes, overrun as they were with rats

and other vermin.

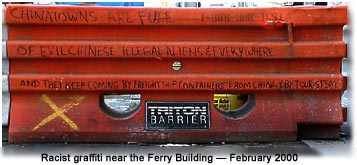

Evil as were these characteristics of the Chinese, they were never

a sufficient excuse for the outrages that were perpetrated upon them. These

bore no relation to the real grievances, but were in a large measure the

unreasoning acts of irresponsible men who were for the most part aliens

themselves. Calmly handled, the Chinese question never would have caused

a disturbance in California. In connection with a violent race hatred,

it kept the state in turmoil for the first thirty years of its existence.

Even today it occasionally recurs to furnish capital for politicians who

are unable to find any other issue. Of late years, however, it has been

very largely superseded in this role by the

Japanese question. Evil as were these characteristics of the Chinese, they were never

a sufficient excuse for the outrages that were perpetrated upon them. These

bore no relation to the real grievances, but were in a large measure the

unreasoning acts of irresponsible men who were for the most part aliens

themselves. Calmly handled, the Chinese question never would have caused

a disturbance in California. In connection with a violent race hatred,

it kept the state in turmoil for the first thirty years of its existence.

Even today it occasionally recurs to furnish capital for politicians who

are unable to find any other issue. Of late years, however, it has been

very largely superseded in this role by the

Japanese question.

In: The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present,

by Henry K. Norton. 7th ed. Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1924.

Chapter XXIV, pp. 283-296.

Return to the top of the page.

|