|

RIPTIDES

The Portals of the Past

By ROBERT O'BRIEN

When I came across a description of the house, I seized upon it and copied

it, because I had been looking for it for a. long time. Until then, I had seen

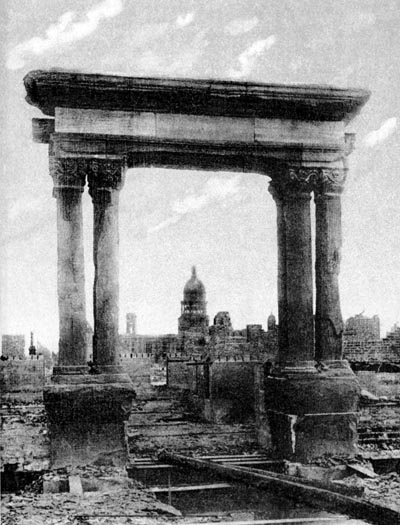

the Portals of the Past beside Lloyd Lake in Golden Gate Park, and had known

they were all that was left of a Nob Bill mansion after the earthquake and fire,

but I had never been able to find out what the rest of the house looked like.

To begin at the beginning, the house was built in 1891 on the southwest corner

of Callfornia and Taylor streets by Alban N. Towne, and it was No. 1101

California street.

There was a curious coincidence in the life of Towne. He was born in Charleston,

Mass., August 8, 1829, the day the "Stourbridge Lion" made her trial run at

Honesdale, Penn. "The Stourbridge Lion" was a locomotive built at Stourbridge,

England, for the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, and that trial run was the

first test of a railway engine in the United States. Towne always felt there was

something prophetic about it, because he spent his entire life, from the age of

26 on, in the railroad business. Starting out as a brakeman on the Chicago,

Burlington and Quincy, he worked his way up to the office of assistant

superintendent of the road. In 1869, the year the Golden Spike was driven, he

became general superintendent of the Central Pacific.

When he was having his many-roomed mansion built on Nob Hill, along with the

railroad barons and the Comstock bonanza kings, he was the Southern Pacific's

second vice-president and general manager. Additionally, he owned some 30,000

acres of California land (much of it in the San Joaquin valley), and was worth

somewhere between $500,000 and $1,000,000.

Towne did not live on Nob Hill very long. In 1896, less than four years after

his house was finished, he suffered a heart attack and died almost instantly.

Until a special funeral boat (the steamer Newark) carried him across the bay for

his burial in Mountain View Cemetery, flags were at half-staff at alI points on

the Southern Pacific road.

The house he built. there on the corner overlooking the city was regarded, it

seems, as the West's best example of what was known as the "Bryn Mawr" style of

architecture. The style was inspired by the English building at the Philadelphia

Centennial Exposition of 1876, and had been extensively copied by Pennsylvania

railroad architects when they designed the Philadelphia suburb of Bryn Mawr

shortly after the exposition. Subsequently, other Eastern communities adopted

the style for their fashionable suburbs. The results were what connoisseurs of

the times termed collections of “high art villas.”

With the passing of two decades, however, the style had become corrupted to the

point where it was scoffingly referred to as “crazy patchwork” architecture, or

"the red-and-yellow craze."• But the Towne house on Nob Hill, it may be assumed,

represented only the cream of the Bryn Mawr design, which means, by contemporary

taste, that it was only slightly less appallingly atrocious than it might have

been. Monstrous, yes, but in a genteel and solid sort of way.

Faithfully, it embodied in its two and-one-haIf stories the best canons of the

Bryn Mawr school: "Honest simplicity in materials-that is real brick, real wood,

real stone, with no shams, no disguising paint or plaster. Let everything be of

some real, visible use. After utility, strive for the picturesque."

The finished product was an elegant study in buff, ecru and cream, whose most

striking feature at first glance was the six white marble Ionic columns of the

Greek portico framing the front door. This portico, it was freely admitted, was

a courageous departure from traditional Bryn Mawr principles. "Perhaps,"

explained the writer of the period, “the particular reason tor the use of this

portico is that it is the only one of its kind in San Francisco."

The first story of the house was of a yellowish, golden brick. The second story

was faced with buff-colored boards. Above that was a cornice of cream - white

wood carved with a conventional wreath design, and the cornice was surmounted by

a white railing, above which rose a sharply pitched roof of ecru-colored

shingles. The roof was broken by several dormer windows, which had eagles carved

In their gables. Over the roof towered four massive chimneys of a reddish-yellow

tone.

There were other details of note: Two stained glass windows, one over the

portico with disc panes, and another larger one with “quaint ellipses and

bull's-eyes.” The first-floor brick wall, incidentally, was decorated by running

bands of carving, which, to Towne and his friends, suggested exquisitely

fashioned embroidery. Over a corner door in the west wall of the house was

another portico shell shaped. “This,” opined the writer, is pre-Revolutionary

style and might have been copied bodily from some of the old country mansions of

Southeastern Pennsylvania."

As

for the interior, it was a pleasing combination of "honest simplicity" and

"artistic elegance." Wherever carved. wood appeared, it was in low relief only.

Fixtures for the open fireplaces included onyx and marble mantels and tongs and

andirons of discreet oxidized silver. As

for the interior, it was a pleasing combination of "honest simplicity" and

"artistic elegance." Wherever carved. wood appeared, it was in low relief only.

Fixtures for the open fireplaces included onyx and marble mantels and tongs and

andirons of discreet oxidized silver.

The cost of the building was $80,000, which was a respectable price in those

days, but which now, of course, is merely trivial.

The house stood there for 15 years, and then, along with the mansions of the

Huntingtons, the Crockers, the Hopkins and the Stanfords, was destroyed, the

disaster leaving nothing standing but the white marble portico. San Franciscans,

sensing that It symbolized an era that had also died, moved it to Lloyd lake,

where it gleams white and graceful and lonely upon the far shore.

This image available as # 1029 in the

store.

Now, upon the corner where it once stood, is a gasoline station, with the

busy California street cars going by all day and Grace Cathedral and little

Huntington Park across the way.

September 8, 1948

San Francisco Chronicle

File # VMSF-0049

Home

|

| |