|

HILL’S “LAST

SPIKE”—HISTORICAL INACCURACIES—

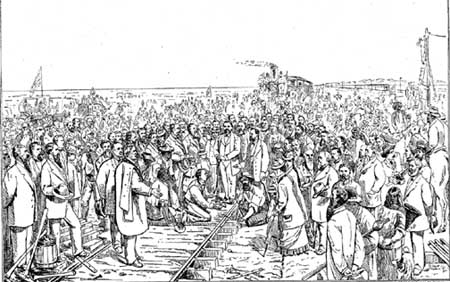

HUMORS AND MINOR INCIDENTS Thomas Hill’s “Last Spike”

has been attracting its crowds of curious visitors for the last two weeks. It

might continue to draw equally well for the coming fortnight, did not inexorable

fate, which directs all such important matters, and the desire of the Solons of

Sacramento to gaze upon its beauties, render it necessary to fold the broad

canvas, and express it, with its group of railroad magnates, into the midst of

the flooded district.

We would be loth to say that Mr. Hill has been negligent in the gathering of

historic material. As a general thing, he has been wonderfully accurate in his

collecting of important facts, and has shown marvelous taste and skill in

translating them into color and form. A few things, however, have escaped his

attention, and as they are personal to ourselves we cannot forbear to mention

them. We alluded last week to one case of forgetfulness in that he had not given

to Frederick Marriott the credit of having presented the last spike. We now wish

to remind the public of a circumstance of even greater moment, which, though

remembered by some, has, during an unusually busy decade, been effaced from the

memories of many by Time’s remorseless fingers, to wit: that from Mr. Marriott’s

lips fell the words of the prayer that immediately preceded the three taps of

the silver hammer on the last spike.

We would very much regret to claim any honor that is not our own, but we do not

hesitate to state that the accounts of the presence and official interference of

the Rev. Dr. Todd on this occasion are as mythical as that gentleman’s literary

achievements. It was to give to the occasion an added solemnity that, at the

suggestion of the real chaplain, the nearest telegraph pole was arranged in the

form of a cross, and that the Hon. A. A. Sargent was painted with a prayer book

in his hand, which he afterwards clapped into his pocket that it might not

embarrass his erect and manly attitude. There is nothing, we may observe in

passing, more important than to keep history and romance apart in art a well as

literature.

We have already described with critical fidelity the salient points of the

painting, but new features strike the observer at every visit. Close inspection

of the locality at the left, where stimulants are retailed, reveals the word

“saloon,” done in the highest style of pioneer sign-board art. The disconsolate

individual in light clothing, who in irreverently neglecting the prayer of

Chaplain Marriott, has been beguiled by the sportive Bedouin of the desert into

a losing fight with the form of the “tiger” called the strap game, takes so

little interest in the subsequent proceedings that he does not even care for a

cigar, pressed upon him by the nut-brown squaw, whose desire for gain has been

cultivated to a high degree of refinement by contact with the whites.

The gold spike was a massive bauble of bullion, worth four hundred dollars, and

it was known at the time that effort would be made by lawless men of the Plains

to get possession of it on account of its intrinsic worth. These attempts were,

fortunately, thwarted by the watchfulness of the police, and by the

thoughtfulness of Governor Stanford, who attached to it a microscopic wire,

after the manner of shrewd urchins who, on the first of April, are wont to

expose in plain view on the sidewalk packages ostensibly precious, which through

the agency of a surreptitious cord, glide into an adjacent area the moment the

avaricious pedestrian stoops to examine them. Of course this is comparing great

things with small, but we follow the essential modes of the critic and logician.

Several groups of thieving conspirators are seen in close conversation in

different parts of the canvas, and two Indians, who distinctly remember their

waylaying overland stagecoaches, and their tying now and then a pony expressman

to a tree for a little harmless tomahawk practice, have their heads together and

are evidently plotting the rape of the spike, which means to them unlimited

whisky and tobacco, and infinitesimal sentiment.

Thus far the great canvas has escaped the serious accidents to which such

valuable works of art are liable. It has not, however, been free from danger.

One day last week the reflector escaped from its moorings near the ceiling, and

swooped toward the canvas like a huge hawk. Or bat, or eagle, bent on

destruction. First it seems to bode malicious mischief to Governor Stanford;

then hovering on the right, it threatened Charles Crocker’s capacious brain,

afterward approaching his more capacious stomach like the sword of a Japanese

official about to commit hari-kari. After this, taking a turn to the left, it

attempted to behead the historically inaccurate clergyman, and finally ended its

alarming gyrations by penetrating the skull of the Indian cigar-seller, and

clipping off the nose of the gambler standing near her. Mr. Hill, who is not

unskilled in surgery of this kind, quietly repaired damages, and the public was

no wiser.

The picture, in which we have taken so deep an interest, will go to Sacramento

on Tuesday, and on Wednesday evening be exhibited in the Assembly chamber at

Governor Perkins’ reception. It is certain to be admired, but whether in these

days of freshet, debris and detritus the sage legislators will do so wise a

thing as to make an appropriation to purchase it and give the State Capitol a

brilliant and suitable ornament is at yet uncertain. But even an invitation to

exhibit it, signed by the Governor and chief officers of the State, is a worthy

compliment to a true gentlemen and admirable artist.

San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser

February 12, 1881

Thomas Hill’s great historical painting, entitled “THE LAST SPIKE,”

and representing the ceremonies observed at the completion of the

overland railway.

San Francisco Newsletter and

California Advertiser

February 5, 1881

History of the last spike

Home

|