TELEGRAPH OFFICE PERCHED ON POLE HOW THE WESTERN UNION BUILT A NEW PLANT IN FOUR DAYS For the first time in its history San Francisco was absolutely without telegraphic communications with the outside world for three hours on the morning of April 18th. Following the earthquake, which occurred at 5:13 a.m., and for three hours thereafter, not a single wire of the score or more usually in operation was in service, and the busy click of the sending instruments was stilled. Ceaselessly through every hour of the day and night messages are speeding to all the most remote sections of the globe, and to have the busy workings of the "tickers" stopped for a minute is an event in telegraphic history. Quick to realize the havoc which could be wrought by so mighty a temblor as that which preceded the big fire. Harry Jeffs, wire chief of the Western Union Telegraph Company, who lives in Oakland, lost no time in reaching the mole for the purpose of testing the scores of wires which emerge from the water at that point. It took the expert but a few moments to ascertain that communication in San Francisco beyond the Ferry building was entirely cut off. Not an instrument responded to his efforts. Turning his attention to the wires extending from the end of the pier to the various stations leading out of the State, Jeffs found that they had been hopelessly "killed" by the great shake. The seriousness of the situation called for quick action, for aside from the great monetary loss to the company resulting from even a short interruption of the service, was the seriousness of being entirely cut off from the outside world. Securing an engine, the wire chief started out from the mole, and climbing poles at intervals along the way, tested the wires to locate the break. In this way he covered the entire pier until he reached the shore at West Oakland. Here at a pole almost at Land's End, after calling on each dead wire separately, he at last received a response from Sacramento, and knew that he had at last found the point of severed communication. Perched on a thirty-foot pole, Jeffs gave the capital the first story of the disaster sent out by wire at 8:30 o'clock in the morning. In quick succession, by means of relays, Los Angeles, Salt Lake, Denver and other places heard of calamity that had befallen the metropolis of the Pacific Coast. For eighteen hours Jeffs stuck to his lofty perch trying with the patience of Job to straighten the tangle in the wires with a small set of testing instruments he had obtained at the pier. This was a heroic task, for the mighty sway of the temblor had brought the wires together, tying them up in great confusion.

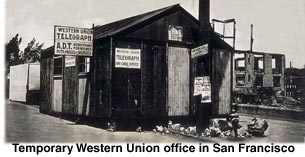

Superintendent Charles Lamb, who was in Goldfield, [Nevada] was communicated with, and St. Paul, Montana, and other western distributing points were ordered to rush telegraphic supplies. Louis McKessick, electrician of the company, was communicated with in Chicago, and within three hours had six carloads of electric apparatus started Westward, with himself in charge. This train arrived on Saturday night, April 21st, and before one could realize it the Western Union Company had an entirely new office in operation in West Oakland. At first when there was only one wire working, the wire chief had prevailed upon a woman who occupied a modest little four-room cottage almost of the water's edge to allow him to place an instrument in her parlor. As other wires were put in commission from Jeffs' pole other rooms were engaged, and finally the good-natured woman was induced to surrender her home entirely, and the company made it worth her while. The place grew too small, however, and within a few hours the company was forced to engage the dining room of an old hotel half a block away on the same street, and in these cramped quarters the Western Union has handled a business three times that of ordinary times. Those unfamiliar with a big telegraphic service cannot appreciate what a mighty task was accomplished in installing wires, switchboards and all the appurtenances necessary to operate eighteen wires in the short time of four days. In addition to establishing an entirely new plant, the company has erected a large corrugated iron and wooden building in West Oakland, and this will constitute the main operating department for months. With the restoration of the wires W.C. McCormick, traffic chief, took charge of the operating rooms and for sixteen and eighteen hours a day directed the dispatching of the tremendous volume of business which fairly poured into the telegraph rooms, threatening at times to swamp the operators. No one who has not visited the department of the Western Union where messages are handled on some such occasion as this can realize the tremendous strain under which a man in McCormick's position labors. There is no let up, no rest. First he must sort and arrange the great batches of telegrams that are dumped upon him every minutes of the day; he must know at a glance the matter that should be put ahead and then he must see that it is routed with the least possible delay and in the most direct way. Only a man of great nervous energy and cool judgment could have cleared away the remarkable accumulation of business, and the Western Union found McCormick the right man to supplement the great work of Jeffs and McKissick. After working eighteen hours on a stretch for days, most men are so worn out that they often drop asleep at the key, but it is said of McCormick that his nervous system was so wrought up with his long- sustained efforts that he could not sleep even after he sought his home for a few hours rest. When

the big earthquake shook the wires, a Pacific Cable operator [in the Postal

Telegraph offices on Market St.] in the confusion was in communication

with Honolulu. The sensitive instrument failed to respond for a short time,

but within fifteen minutes after the shake service was completely restored.

Return to the 1906 Earthquake Exhibit.

|

By

Wednesday afternoon the break between the pole at Land's End, West Oakland,

and the pier had been closed with one though wire. The following day, Thursday,

three more wires were restored, and on Friday eighteen were in full operation

front the pole at which the break was first located. This did not mean

the restoration of the Western Union's service by any means, for with the

burning of the company's building in this city all its instruments, batteries,

and appurtenances were lost, and the company was therefore as badly off

as if the wires had not been restored. From his operating office on the

pole however, Jeffs was instructed to call upon all the near-by towns

and cities to rush instruments that could be spared to this city.

By

Wednesday afternoon the break between the pole at Land's End, West Oakland,

and the pier had been closed with one though wire. The following day, Thursday,

three more wires were restored, and on Friday eighteen were in full operation

front the pole at which the break was first located. This did not mean

the restoration of the Western Union's service by any means, for with the

burning of the company's building in this city all its instruments, batteries,

and appurtenances were lost, and the company was therefore as badly off

as if the wires had not been restored. From his operating office on the

pole however, Jeffs was instructed to call upon all the near-by towns

and cities to rush instruments that could be spared to this city.